In an extraordinary judgment, the Court of Appeal have declared that an element of the assessment of Universal Credit is so irrational as to be unlawful. Gareth Morgan has explained, at some length, how Universal Credit manages to take information about regular, predictable incomes and rent, and convert that into an irregular and unpredictable stream of income. The point of contention in this case is a small part of that, but the problem the court was looking at is pretty straightforward. Banks do not operate on bank holidays and weekends, and the Universal Credit assessment ignores that. That has meant, for people unlucky enough to have an assessment marked down for an awkward date, that regular income will be counted as too high, or too low, and the amount they receive will fluctuate wildly. The court was not impressed by the DWP’s arguments that changing the assessment in this case would be expensive or inconvenient.

“The Secretary of State for Work and Pensions’ refusal to put in place a solution to this very specific problem is so irrational that I have concluded that … no reasonable SSWP would have struck the balance in that way. “

How, we might reasonably ask, did the DWP get in this mess? There have been three recurring problems. First, Universal Credit was designed by people in a mental bunker, determined not to share, consult or engage people who understood how benefits work – including their own front-line staff.

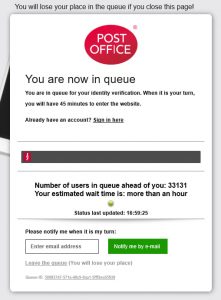

Second, the system has been built around the capacity and convenience of the ICT, rather than the tasks that needed to be done. The technology has never been capable of doing the sort of things that are needed to run a system properly – the failure of the verification system is an illustration. The process we now have in place is cumbersome, complex, slow, very expensive and difficult to change. We did things faster, and cheaper, forty years ago.

Then there is the failure of the safeguard, which depends on the scrutiny of regulations by the independent Social Security Advisory Committee. I’ve been critical in the past of the SSAC’s approval of policies and regulations that I cannot believe would stand the test of judicial review, such as mandatory reconsideration or the sanctions regime. (Both policies violate the centuries-old principle of audi alteram partem, or natural justice: no legal penalty should be imposed without first giving the person sanctioned the opportunity to be heard.) The problem is, I think, that the SSAC tries to reach decisions through consensus, and an insistence on compromise is fundamentally inconsistent with the role of independent expert advisers in identifying specific issues that fall within their area of expertise. Illegality should not be treated as being open to negotiation. The bulk of the SSAC’s work is confidential, but in the light of this judgment they need now to review whether they had identified the fatal legal flaws in the regulations, and if not why they failed to do so.

I’m not keen on Gareth Morgan’s proposed fix for the problem of dates, which is designed to tweak the assessment for the people affected while minimising disruption to the information that the DWP gathers. By all means, let’s disrupt this. Real-time assessments are beyond our capacity to deliver; whole month assessments, delivered at the end of the same month, lead to radically unstable income streams; individual variations in payment arrangements lead to complexity and confusion. I lean towards the French system, which is to use, as far as possible, retrospective information about means, and the same predictable, common dates for everyone: it makes a huge difference to the predictability and stability of income.