The first Hallett report on the management of a pandemic is disappointing. It’s wordy and over-blown, but that’s not the main problem. Consider this central, first recommendation for action:

“Recommendation 1: A simplified structure for whole-system civil emergency preparedness and resilience

The governments of the UK, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland should each simplify and reduce the number of structures with responsibility for preparing for and building resilience to whole-system civil emergencies.

The core structures should be:

• a single Cabinet-level or equivalent ministerial committee (including the senior minister responsible for health and social care) responsible for whole-system civil emergency preparedness and resilience for each government, which meets regularly and is chaired by the leader or deputy leader of the relevant government; and

• a single cross-departmental group of senior officials in each government (which reports regularly to the Cabinet-level or equivalent ministerial committee) to oversee and implement policy on civil emergency preparedness and resilience.”

The idea behind this seems to be that the way to be effective is to give the responsibility squarely on the busiest, most senior figureheads possible. That is hopelessly naive – and it’s what led to the effective dereliction of duty when the Prime Minister couldn’t be bothered turning up to routine meetins of COBRA. Picture the scene. Nothing more happens for 25 years, and then we get hit again. What will those high-level, cross-departmental groups have done in the meantime? They’ll take it seriously at first. Then it will become more routine. There’ll have been at least two, possibly three, new governments, and far more responsible ministers. There’ll be changes at the level of supporting departments. Senior staff will retire. And someone, someone, won’t treat this as a priority any more.

The crucial test of any administrative structure is not what happens when everyone has good will, competence and commitment. It’s what happens when things go wrong.

The second complaint: Hallett thinks that our government isn’t centralised enough.

“It is therefore necessary to place in charge the only government department that has the power and authority necessary to take the lead – the Cabinet Office. It has the decision-making power of the Prime Minister and the oversight and ability to coordinate the activities of the whole government.”

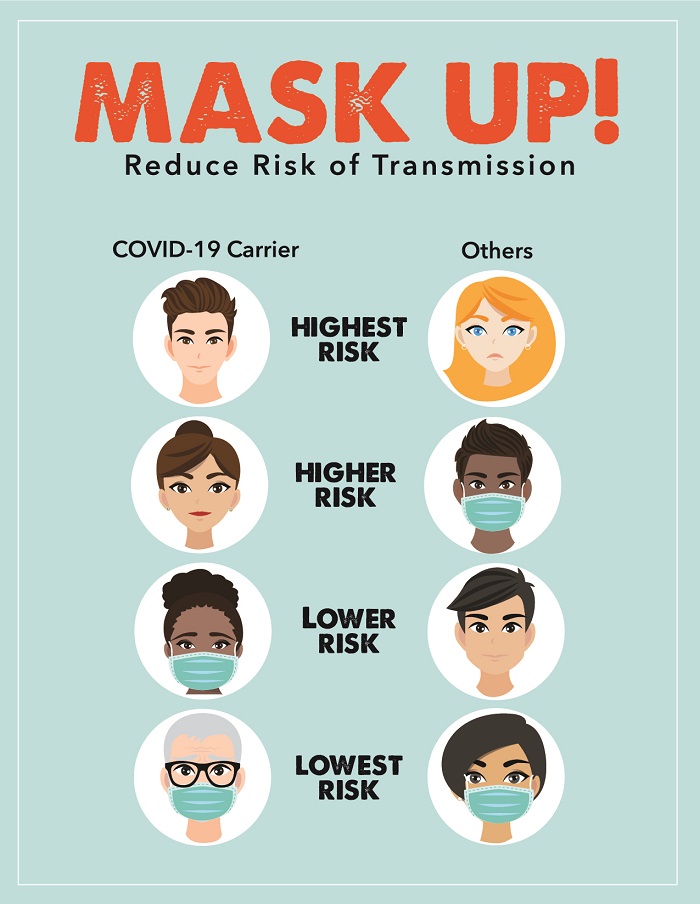

This is absurd – and dangerous. Hallet complains about ‘groupthink’, but her proposals are a recipe for more of it. In the pandemic, decisions were highly centralised. That’s one of the principal factors which led to the single-track policy, assuming that this disease would be like flu. People who knew how to identify the spread of disease, people who knew local areas and local systems for distribution, were sidelined. And later, when new evidence emerged to say that the official advice (Hands-Face-Space) was off-beam – because the disease was airborne, not mainly spread by droplet – the ‘leaders’ couldn’t bring themselves to change the advice.

We’ll get on to issues about the conduct of the response in due course, but that’s for a later report.