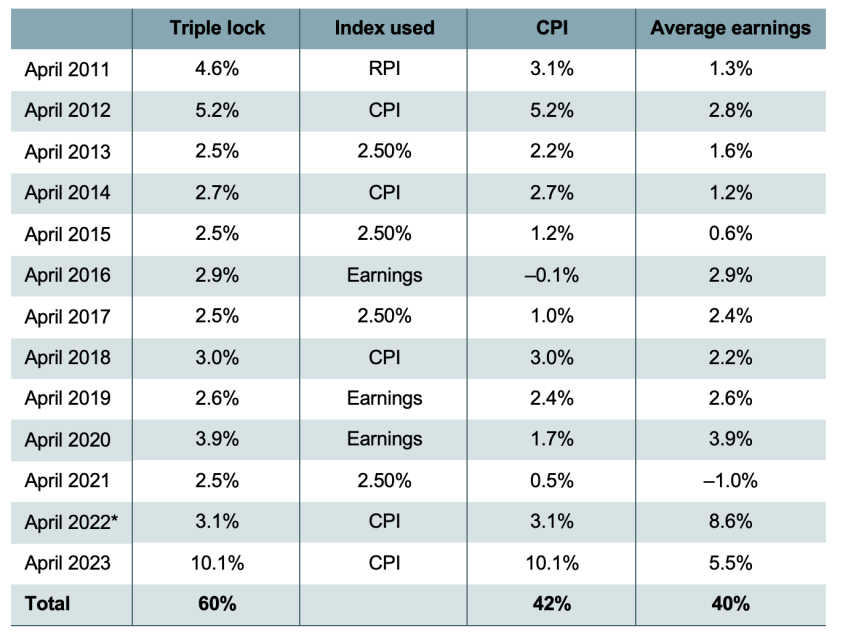

The ‘triple lock’ is the name given to a commitment to maintain and improve the value of state pensions. The table comes from a recent report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

In the course of the last twelve years, this has meant that pensions have increased by a nominal 60%, while if they had only increased by inflation, they would be up 42%. Putting that another way, pensions have risen by 12.7% over inflation (that is, 160/142), which in real terms is 1% a year.

One might suppose that ratcheting pensions up, however slowly, was a praiseworthy thing to do, but the principle has come under fire from those who claim that it represents an unsustainable commitment. The criticism has been fed by the IFS report, which argues that it creates ‘uncertainty’ about the future value of state pensions, and that if it is left in place till 2050, it will increase the value of the state Pension from about 25% of median earnings to something between 26% and 32%.

The first of these arguments is, frankly, codswallop. The benefits system is in a parlous state: the main ‘uncertainty’ it is creating is whether or not people will be able to eat. Improving the value of the pension does not increase uncertainty; it reduces it. If we are genuinely concerned about the narrower problem of how people plan their pensions for the future, the main ‘uncertainties’ come from the govenment’s eccentric reliance on means-testing and the desperate problem of paying for social care.

The second argument invites the obvious retort – so what? A modest increase in the value of pensions, relative to the median wage, is surely a good thing. The UK’s treatment of pensioners is, by international statndards, parsimonious. Consider this graph from the OECD. It puts the percentage of GDP spent on pensions in the UK at 5.1%. The Office for Budget Responsibility, which works on a slightly different set of definitions and takes into account a few extra benefits, estimates that this year, the percentage will be – try not to be too shocked – 5.3%.

https://data.oecd.org/socialexp/pension-spending.htm

The State Pension provides, at best, a modest basic income. The (somewhat limited) success of the triple lock is something to applaud, not to denigrate. One might wish that the the same approach could be taken for the painfully inadequate benefits offered to people of working age.