The documents released to John Slater are now available on the FoI website, What do they know. Be warned that the Programme Risk files (numbered 3-6 in this list) are massive, so I’ve uploaded a smaller version here (one file of 6Mb instead of four totalling over 25Mb).

- Issues Log http://files.whatdotheyknow.com/request/…

- Milestone Plan http://files.whatdotheyknow.com/request/…

- UC Programme Risk Part 1 http://files.whatdotheyknow.com/request/…

- UC Programme Risk Part 2 http://files.whatdotheyknow.com/request/…

- UC Programme Risk Part 3 http://files.whatdotheyknow.com/request/…

- UC Programme Risk Part 4 http://files.whatdotheyknow.com/request/…

Last week, I outlined two rather different accounts that have been given of what went wrong. The first suggested that the project was going according to plan when the Cabinet Office intervened and blew everything out of the water. The second was that the DWP were aware of a series of problems, but those problems were not admitted to publicly and they were not satisfactorily addressed. Looking at the papers in more detail, I’m inclined to a third, quite different conclusion. The milestones laid out in the documents were largely met – but they were woefully inadequate to deal with a scheme of this complexity. The issues which were recognised within the DWP – such as the problems of potential fraud, identity checking or the low morale of staff – don’t begin to plumb the depths of the practical problems that the scheme needed to overcome. I complained in 2011 that the scheme was half-baked. It was worse than I thought.

I’m going to pick out a small point as an illustration. The scheme aimed to pilot the use of RTI – real time information – from employers. There is a minor risk noted, that

“Employers may not be ready to take part in the RTI main Migration (from April 2013). The Comms activity to target the mass market may not reach some employers. Employers may not have the relevant new software in place.”

In retrospect, this may seem thin – but it wasn’t good enough then, either. The review team made three basic mistakes. The first problem concerns the impossibility of partial implementation. It would be possible to see how the scheme worked only if all employers relevant to a claim were included in the scheme – because partial information could not be enough. The second problem was the belief that the systems would be in place to back up the processing of information – they weren’t – and that the agency’s main task would be chasing laggards and improving communications.

Beyond those two, however, there was a deeper problem, intrinsic to the design. We know from public statements that the design team was working on the assumption that claimants followed predictable pathways. They took it for granted that people would be moving between worklessness and stable, single employment. However, people on low incomes, working in a ‘flexible’ labour market, have to be expected to move between states, often covering several employers, including some who may not be cooperative or explicit about what is happening. Many people’s incomes go up or down rapidly and unpredictably. The whole point of this scheme was supposed to be that it would offer claimants a personalised, seamless experience in real time. To do that, there had to be a system that followed the employee, not the employer. It seems from these papers that they hadn’t even started to think about how that could be done. As far as I can tell, long after the reset and redesign, they still haven’t grasped the nettle – currently, everything depends on the individual claimant reporting changes as they happen. There has been no point during this process when the systems in place have promised to be minimally capable of operating as intended.

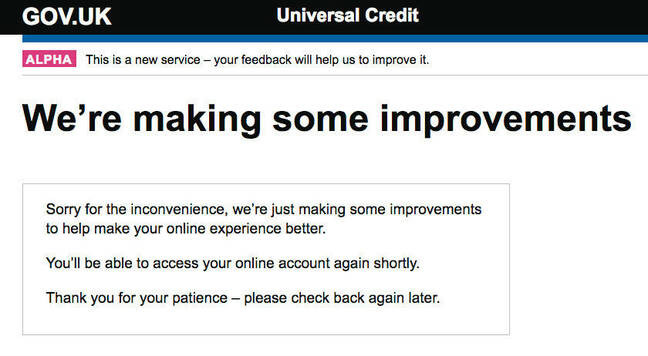

The Register reports a small glitch in the Universal Credit scheme. Access to the online system was closed for more than 24 hours after an upgrade went wrong. A DWP spokesperson described this as a ‘minor issue’.

The Register reports a small glitch in the Universal Credit scheme. Access to the online system was closed for more than 24 hours after an upgrade went wrong. A DWP spokesperson described this as a ‘minor issue’.