Although the EU has been behaving badly about the Brexit negotiations, they have reason to complain about Britain, too. They’re right, first, to say that Britain’s position papers are too vague to be any use. Britain offered 16 pages on trade, for example, recently supplemented by another 11 pages on continuity. It’s not difficult to know what a successful trade agreement looks like. The agreement with Canada, CETA, runs to nearly 1600 pages. What the UK had to do – and it’s had 15 months to do it in – was to begin with those 1600 pages, identify which terms are acceptable to Britain (they are all, after all, already acceptable to the EU), and then work on the differences. That would still be a lot of work, but at least there’d be a meal on the table rather than a bowl of twiglets. Britain can hardly complain that trade is not being discussed if they’ve not offered any points for discussion.

The EU negotiators are right, too, to identify key issues besides trade: citizens’ rights, Ireland and treaty obligations. The UK’s concerns are difficult to decipher; the latest position paper relates to the confidentiality of official documents, which suggests that government ministers are more concerned with covering their backs than they are with getting on with the business. Where the Commission is behaving badly is to say that nothing else gets discussed. The EU also has treaty obligations. Article 50(2) states that

the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union.

Whatever happens about the bill, the EU has no right to refuse to discuss the future relationship.

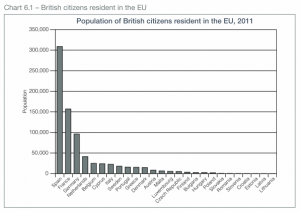

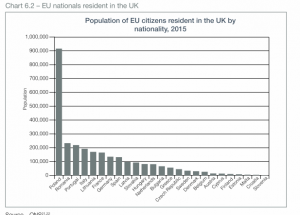

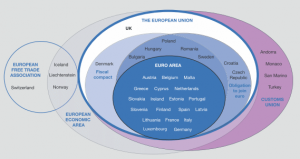

Two of the three items the EU is starting with are, in fact, about that relationship: Ireland, and citizens’ rights. The Irish border is difficult, but not intractable, because different elements can be separated out and dealt with differently: for example, Switzerland is not part of the customs union or the EU but is part of Schengen. Citizens’ rights is much the more complex problem, and neither of the parties has shown any inclination to acknowledge that UK citizens resident in the UK are also currently citizens of the EU, and many will face the same sort of problems with split families, cross-border care, pension rights or interrupted periods of residence that people now in Europe or other nationals now in the UK will face.